Greenwood Corvette at the 2024 Monterey Motorsports Reunion

Seeing (and hearing) a widebody Greenwood Corvette at a race track is incredible. While you might assume that these cars are all about their 700+ horsepower big block engines and less advanced than their competition like the Porsche 935 and BMW 3.0 CSL, these cars were very advanced, and developed by many people who built some of the best racing Corvettes of the past and future. John Greenwood was a car enthusiast from a very young age and started street racing on Detroit’s Woodward Avenue when he was only 15. He purchased a Corvette in 1964, the first of many Corvette’s he would modify. After winning his first autocross event with no training, he started road racing and was a driver and engineer, building and racing his own Corvettes. In 1969 he started his own racing team, eventually winning the 1970 and 1971 SCCA championship in his C3 Corvette. Greenwood then started a race shop called Auto Research Engineering, building cars for many of his street racing rivals. After winning a endurance race for cars on street tires in 1971, BF Goodrich sponsored him to enter three Corvettes on their Radial/TA street tires for five endurance races, including Daytona, Sebring, and Le Mans, where they would be very competitive against the slick-tired opposition. The Greenwood Corvettes soon developed a reputation as winners, and fan favorites due to their extremely loud engines.

The birth of IMSA and the widebody Corvette

Under the skin of the widebody Corvette

The IMSA championship was based on the FIA’s Group 2 and Group 4 rules, but less strict- much wider fenders and larger engines were allowed. Greenwood’s current Corvette’s struggled to put down all of their 600+ horsepower, so work began on a new car for 1974 that could take advantage of the new IMSA rules and race in the Trans Am championship, the SCCA’s pro series. While Greenwood was a privateer, the new cars development had skunkworks support from GM, who had no factory GT racing effort at the time. The body was designed with help from none other than Zora Arkus-Duntov, along with GM designer Randy Wittne, and Gary Pratt who would later start Pratt & Miller. The finished car had wide-body fenders that made over 1000 pounds of downforce at 200 MPH, that also cooled the brakes through the rear vents and reduced drag significantly. However, the car had quite a few aerodynamic elements that were in a grey area regarding the rules. In an attempt to sneak them past the stewards, a illegal floor (what would be known as a diffuser now) was installed under the car. This was immediately removed as the team had expected, and the stewards didn’t bother looking at the body, allowing it to race.

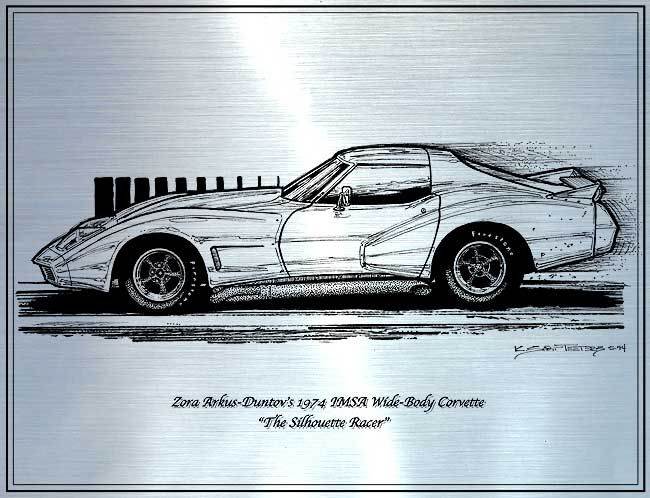

“The Silhouette Racer”, Zora Arkus-Duntov’s original plan for the widebody Green wood Corvette. Some debate exists on whether this was a project started by Zora, but it is believed that it was Greenwood’s test mule that was being tested at GM’s proving ground.

The chassis was based on a heavily modified C3 Corvette frame, which was modified to fit the engine more than a foot further back than stock. The frame was than acid dipped and then reinforced with a roll cage designed by the legendary Bob Riley, who helped design the GT40 MKIV, the Roush Mustang IMSA GTO, and many other significant American racecars.

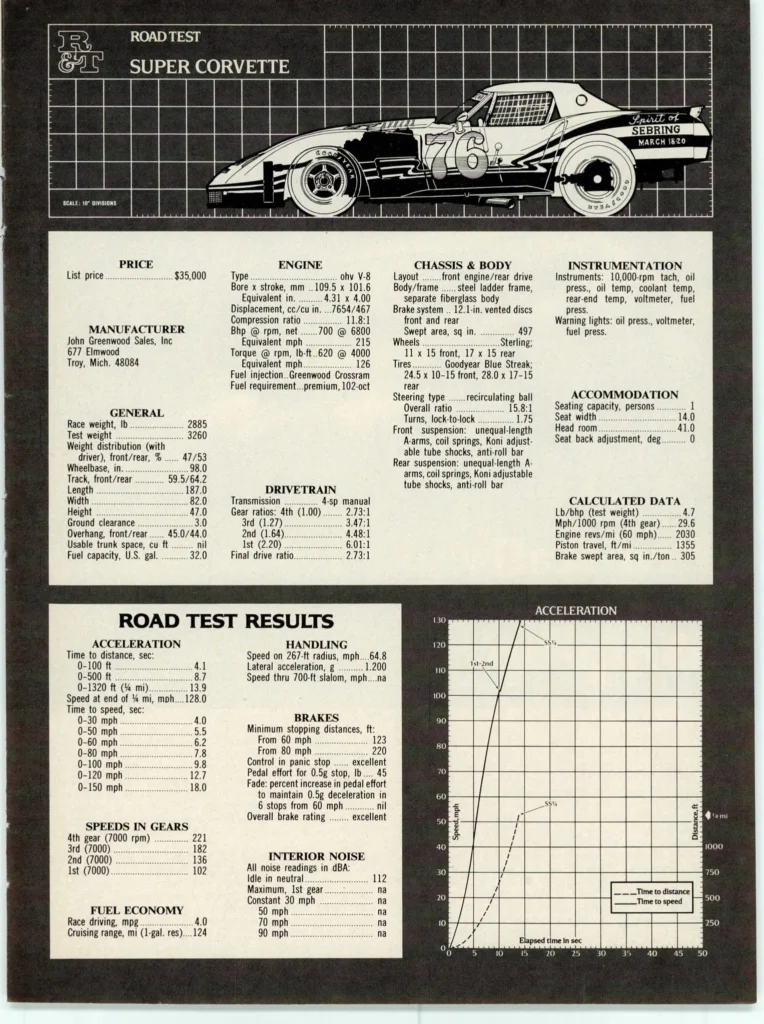

Road & Track, March 1976.

The suspension was kept stock at the front except for new bushings and geometry, but the rear suspension was an all-new independent unit to significantly reduce squat under braking and acceleration. The car used a 4-speed Muncie M22 transmission, known as the “rock crusher” in racing circles for it’s incredible durability. Massive Wildwood NASCAR-spec brakes were the only brakes that Greenwood trusted to reign in the cars endless power. The engine was the centerpiece of the car, a ZL1 spec big-block V8 with many upgrades. The engine featured in the Road & Track test was a ZL1-spec with an overbore to increase capacity to 476 cubic inches. Other upgrades included a upgraded crankshaft, Carrillo rods, Isky roller rockers, and a reworked camshaft. The most potent upgrade was the custom fuel injection system with a crossram magnesium manifold that took Greenwood three years to develop. All this resulted in a monstrous 700 horsepower at 6800 RPM, and 620 pound-feet of torque. A Road & Track test from 1976 where the Greenwood widebody was pitted against a stock C3 Corvette, the Greenwood car idled at 112 decibels, enough to break R&T’s sound meter. If you’re wondering what that sounds like, check out this video of Jordan Taylor racing the “Sprit of America” Corvette and unleashing hell with his right foot against a field of Porsche 935’s at the 2019 Monterey Reunion.

The car weighed about 2885 pounds with fuel, much heavier than it’s BMW and Porsche rivals, but it more than made up for it with all of it’s power. In a the Road & Track comparison test, the Greenwood widebody did a 13.5 second quarter mile which was quite quick for it’s era. However, the car had longer gears for the Daytona IMSA race, and the car supposedly could have done a blistering sub-10 second quarter mile at over 160 MPH with shorter gears. The cars top speed was also mind blowing, hitting 236 miles an hour at the Daytona finale, making it the fastest ever car on the high banks, and reached over 220 miles an hour on the Mulsanne Straight. The widebody Corvette was unveiled at the Detroit Auto Show in 1974, although the car wasn’t fully finished yet. Greenwood built three cars for his team, but to help fund the cars development and his own racing endeavors, he would sell you a “customer car” for $20,000 (without an engine). The customer cars were less advanced, with a less bespoke frame and standard front suspension, though many customer cars were upgraded to coilover suspension later. Nine customer cars were built, all at Greenwood’s shop in Michigan.

Going Racing

John Greenwood and John Bishop saved the 12 Hours of Sebring from being canceled due to a recession in 1974, and helped fund renovations that kept the track to FIA standards

The Greenwood widebody was very competitive immediately, but reliability issues kept the car from it’s first IMSA win until the Daytona 250 IMSA finale. The Vettes were unstoppable in qualifying, taking 11 pole positions in 1975 against the dominant Porsche’s and BMW 3.0 CSL. But reliability continued to be the cars weak point, and the blistering pace was rarely converted into wins. The Corvette did win the Talladega and Daytona 250 races, where it could use all of it’s 700+ horsepower. The Trans-Am championship was much more successful, with John Greenwood and Sam Posey winning the 1975 championship in the “Old Blue” Corvette.

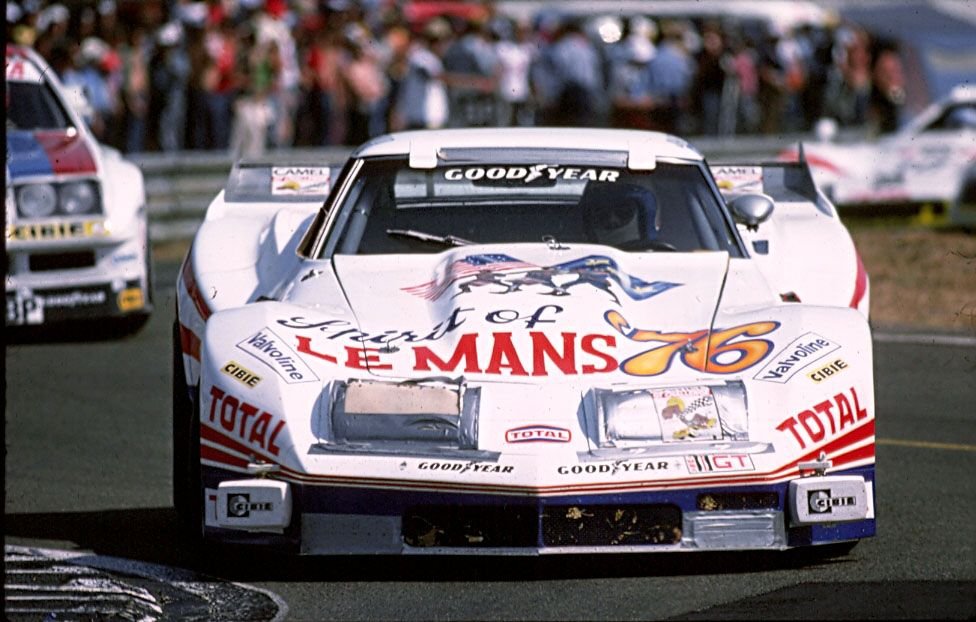

The “Sprit of Le Mans” at Le Mans, 1976

Possibly the most iconic moment of the widebody Corvette’s racing career was the attempt at Le Mans 1976. Greenwood had raced Le Mans before in 1973 with his “Stars and Stripes” C3, a 1969 L88 Corvette with a ZL1 engine installed making around 700 horsepower. It hit an incredible 215 miles per hour on the Mulsanne straight, a GT class record. The car retired after only four hours, but the fans loved the deafening roar of the car and Greenwood would be back. In 1976, the oil crisis was in full swing, and the grid at Le Mans was much smaller than previous years. The original “Stars and Stripes” Corvette was a fan favorite at Le Mans several years before, so the French government paid Greenwood $55,000 to field another Corvette at Le Mans. This was potentially the first time a team was ever paid to enter Le Mans. Several other cars came from IMSA to race in their own class, and even NASCAR brought two cup cars. The car Greenwood entered was chassis CC007, originally built for racer Rick Mancuso who planned to race Daytona and Sebring, but the car didn’t arrive until after Sebring. Greenwood convinced Mancuso to lend him CC007 at Le Mans, where Greenwood, Mancuso and F1 driver Jacques Lafitte would drive it. Quite a few GM engineers were involved in getting the car ready for Le Mans, and Chevrolet promoted the car even though it wasn’t a factory entry. Mancuso couldn’t make it to Le Mans however, as his father wouldn’t give him the time off from his job at his dad’s Chevy dealership. He was replaced by French rally driver Bernard Darniche. Greenwood put the car 9th on the starting grid with a 3:54.6 lap, hitting over 220 MPH and beating all of the other GT cars except for a BMW 3.5 CSL Turbo and the works Porsche 935. Sadly, a fuel leak ended their race only 29 laps in. While their race was short lived, the car was loved by the fans for it’s ear-shattering noise and wild bodywork.

The Supervette

The first “Supervette” built for JLP Racing. Photo: Canepa

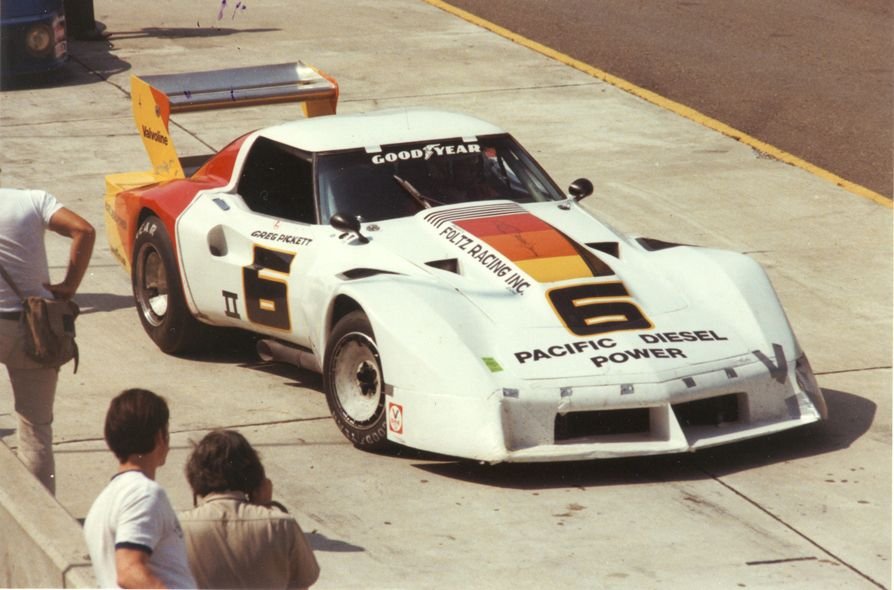

By 1977 however, Porsche and BMW were building low volume extra advanced cars like the 3.5 CSL and the 935 that their American rivals couldn’t keep up with. as John Bishop said, “It occurred to me that Porsche was abusing the FIA Group 5 rules with the turbo-powered 934 and then the 935 with its wilder bodywork. The Group 2 and 4 rules limited what you could do with the bodywork but not so with the Group 5 rules. There was total disregard for the future of the class. We couldn’t ban the Porsches. So, I figured we’ll just do what they’re doing.” Thanks to lobbying from Greenwood and others, IMSA created the AAGT “All American GT” class. These regulations intended for tube-frame, widebody American GT cars that would be competitive against the Porsches. Greenwood’s AAGT car was the “Supervette”, a full tube-frame car designed by Bob Riley. These cars used a all-aluminum big block engine from a Shadow Can-Am car, making over 700 horsepower. The first full tube-frame Corvette was known as “The Winged Thing” and was raced by Greenwood for only three races before it was sold to Greg Pickett, and then Jerry Hansen who won the 1978 Trans AM championship in it.

The other “Supervette” as raced by Greg Pickett

The other car was sold to the infamous John Paul Sr. of JLP Racing, who were famous for their homebuilt 935’s, and more famous for finding their team through drug smuggling. Just like the previous widebody car, the Supervette was incredibly fast but couldn’t beat the reliable Porsche 935’s. The car had several podiums, but a win always evaded them. By the 1980’s, Greenwood was struggling to fund his own racing efforts, and began modifying road-legal Corvette’s. While he built other racing Corvette’s later, none were as memorable as the widebody car. The widebody Greenwood Corvettes are still some of the most iconic GT racers of the 70’s that flew the flag for racing Corvette’s when GM had no factory team, and are always a crowd favorite wherever they appear.